Hardware not enough

Knowledge gaps undermine just transitions, so aid must also build soft infrastructure

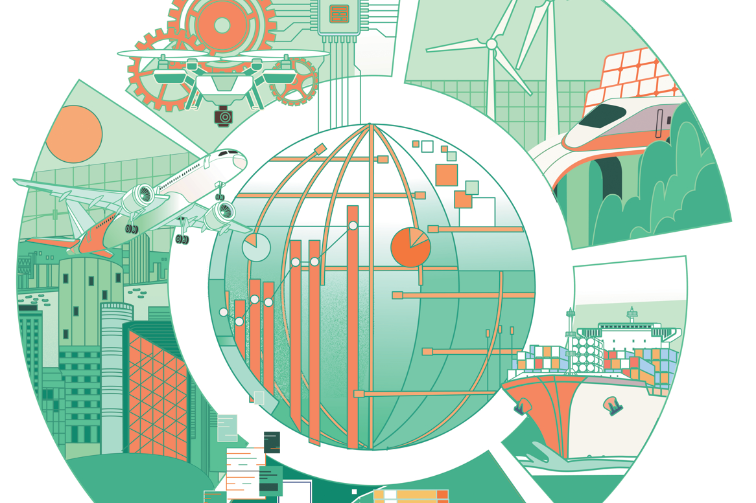

The green transition is often framed as a hard infrastructure contest: who can build more renewables, upgrade grids faster and scale clean manufacturing at lower cost. Yet one of the most consequential sources of inequality in the green transition is far less visible: unequal access to information and knowledge. The green transition is not only technology-intensive, but also knowledge-intensive. When high-quality research, data and policy analysis are inaccessible or unaffordable, countries and communities are effectively locked out of the debates that determine transition rules, finance terms and distributional outcomes. That is not a technical inconvenience, but a structural barrier to a just transition.

Evidence — data, modeling, policy analysis and institutional learning — is the foundational asset of modern governance. It shapes credibility, coalition-building and negotiating leverage when rules are being written on climate finance, carbon markets, transparency, technology cooperation — and increasingly on product standards and trade-related climate measures.

When countries and groups cannot readily access, generate and communicate high-quality analysis, they face a structural disadvantage in shaping the very rules that later govern their development options. The result is predictable: policies risk favoring what is easiest to measure and fund, rather than what best protects livelihoods and equity.

The annual United Nations Conference of the Parties on Climate Change illustrates how this plays out in practice. Climate talks are vast, technically dense and operationally demanding. COP28 in 2023, the largest COP ever held, recorded 83,884 in-person participants plus 2,089 online, taking attendance to almost 86,000. In a negotiating ecosystem of that scale, influence is not determined solely by formal standing; it is shaped by the ability to follow parallel tracks, interpret legal and technical drafts in real time, mobilize evidence quickly and stay engaged across years.

In practice, this means that voice is shaped by capacity. Parties and stakeholders who can access high-quality evidence, translate it into negotiating positions, and respond quickly to evolving text are far more likely to be heard. Those without access to research, data, trusted analysis and the institutional support to use them are often sidelined — even when their interests are most affected by climate risks and transition costs. Without deliberate investment in these "soft" capabilities, international negotiations will continue to privilege the well-resourced, and the promise of a just transition will remain harder to deliver.

Capacity constraints show up most clearly in how countries can follow the process. When multiple negotiating tracks run in parallel, delegations with limited analytical and institutional support cannot cover key rooms, respond quickly to draft text, or sustain engagement across sessions.

The gaps are not limited to governments. Many non-state actors — research institutions, youth groups, community representatives, small and medium-sized enterprises, and industry associations — face similar barriers in time and expertise, accreditation and language, and access to reliable evidence and policy platforms. When these voices are missing, international processes lose on-the-ground insights and legitimacy. Domestic decision-making also becomes less inclusive, undermining social acceptance and the prospects for a just and equitable green transition.

This is why international development aid must treat "soft infrastructure" as a priority, not an afterthought. Soft infrastructure is the institutional and human capability that enables countries and communities to access and interpret evidence, formulate positions, negotiate effectively and implement outcomes credibly — and, crucially, to have their voices heard in the processes where transition rules are set. Since the green transition is knowledge-intensive, ensuring access to knowledge — and the capacity to use it — must be part of climate action.

However, it would be a mistake to frame capacity gaps as purely technical deficits caused by limited access to knowledge, finance or expertise. In many developing countries, these gaps are also the outcome of weak governance — fragmented mandates across ministries, inconsistent enforcement, and limited transparency and accountability. Weak governance slows position-setting at home, weakens continuity in negotiating teams and reduces credibility in implementation. In practice, that can compound disadvantage: it limits influence in negotiations and makes it harder to convert international outcomes into durable domestic delivery.

For international donors, the implication is that capacity building for the green transition cannot be treated as a sequence of short trainings paired with short-term funding. It requires a deliberate focus on soft infrastructure that combines knowledge access, institutional strengthening and governance capability.

Where soft infrastructure is needed, emerging and developing economies can themselves be donors of knowledge. For example, China's experience in building and operating a national emissions trading system offers practical lessons for other emerging and developing economies, particularly on the soft infrastructure of data, monitoring and compliance. Sharing these lessons through demand-driven South-South cooperation — adapted to local conditions — can help countries build credible climate policies more quickly.

Delivery approach matters as much as content. Capacity building works best when it strengthens a genuine "sense of ownership" — so partner countries define priorities, shape solutions and lead implementation, rather than receiving pre-packaged "best practices" from outside. Donors should start by listening: working with partner countries to identify the constraints they face in practice, then providing longer-term support to strengthen the basic systems that make policy credible and finance usable.

This aligns with long-standing development effectiveness principles: the OECD's Paris Declaration emphasizes that capacity development is the responsibility of partner countries, with donors supporting locally led strategies rather than substituting for them.

Youth should be a priority in this agenda, not an optional add-on. In many developing countries, young people face the highest barriers to accessing knowledge and entering the policy spaces where rules are shaped — yet their perspectives are essential for legitimacy and innovation. Initiatives show what is possible when barriers are lowered and young people are given credible platforms to contribute. Donors should therefore invest in youth voice and participation, including open access to data and research, mentoring and training pathways, and sustained support that enables young experts to contribute to policy design and international engagement rather than remaining spectators.

Greater coordination among donors can create synergy and avoid duplication. In the green transition there is often more shared interest than geopolitical competition, and practical cooperation — such as Australia and China coordinating capacity-building support for Pacific nations — can benefit all partners.

The green transition will only be widely accepted if it is seen as legitimate — and legitimacy depends on inclusion. Building solar farms and transmission lines is vital, but so is building the soft infrastructure that enables developing countries, disadvantaged groups and youth to access knowledge, shape rules and deliver outcomes credibly. In a world where the rules of decarbonization are increasingly set through international governance, focusing development aid on knowledge access, ownership-based institution building and governance capability is not charity. It is a prerequisite for fairness, trust and long-term success.

The author is a professor of energy economics and sustainability, the research principal at the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney and the president of the International Society for Energy Transition Studies. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.