Writer's quest to record Beijing's fading memories

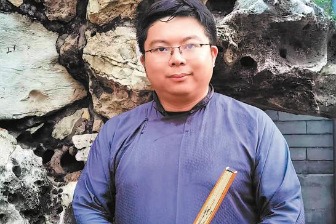

From his study in a Dongcheng district hutong, Hou Lei can see the Drum Tower — a landmark of the Beijing Central Axis, which was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in July 2024. For Hou, a 43-year-old researcher, the prestigious title is only half the story.

While the world celebrates Beijing's imperial grandeur, Hou is busy documenting the "ghosts" of the city: a forgotten jockey club, the specific taste of fermented tofu, and the stories of elderly residents who once assisted the great historians of the last century.

"If local writers don't record the smallest and most hidden details, they will disappear," Hou said.

Among the most striking "overlooked" chapters in Beijing's history is horse racing.

Few people today realize that Beijing once had a jockey club and a horse racing track at its heart, said Hou, revealing a forgotten chapter in a city better known for its imperial palaces and hutong alleyways.

"Horse racing and equestrian performances were once a popular form of entertainment in Beijing," he added.

Speaking ahead of the Year of the Horse, he said such events typically began after Spring Festival and ran until the following winter.

According to Hou, horse racing in Beijing dates back to the Yuan Dynasty (1206–1368), and had become an international sporting event by the 1920s. It is one of many lesser-known cultural threads woven into the capital's long history.

Hou has built a reputation for uncovering these overlooked details, often focusing on the everyday lives of ordinary Beijingers. In his books and lectures on the Spring Festival, he highlights traditions rarely shown on television, including the four dishes that even the poorest families once insisted on preparing for the holiday: mustard root and stir-fried pickled cucumber, tofu with fermented black beans, and a pork and bean jelly known as roupidong.

"These were modest dishes, but they mattered," Hou said. "Even families with very little made sure they appeared on the table."

His writing draws heavily on childhood memories and stories passed down by his grandmother. Hou's family has lived in Beijing for more than 150 years, and he still resides in a hutong — narrow alleyways that form one of the city's oldest residential landscapes.

"Unlike many Beijingers who moved into apartment buildings, I stayed," he said. "I live here to write and research."

He often walks through nearby hutong, photographing former residences of influential figures such as reformer Kang Youwei (1858-1927), architect and writer Lin Huiyin (1904-1955), and Chen Duxiu (1879-1942), a key figure in China's New Culture Movement.

On one such walk, Hou met an elderly man who told him he had once assisted historian Gu Jiegang (1893-1980) and was still dedicated to preserving his research.

"That encounter reinforced my belief that Beijing's hutong are treasure troves," Hou said.

Hou's own books include Beijing Smoke-like Trees, which explores daily life in the city, and The Record of Beijing's Prosperity, a study of its historical depth. He has also recently edited Anecdotes of the Yan Capital, a collection of research on Beijing by Qu Xuanying, the son of a senior Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) official.

"Prose demands discipline and inner strength," he said. "The more you write, the harder it gets because you must keep surpassing yourself."

Still, he said Beijing's cultural richness leaves plenty to explore. "People have been writing about Beijing since the Yuan Dynasty (1206–1368),"Hou said. "Different writers capture its people, its flavors and its stories. I will keep writing in the Beijing dialect, continuing to uncover the memories buried in the city."

yangcheng@chinadaily.com.cn