Coaxing secrets from drifting art

Made-for-export oil paintings offer a rare snapshot of a lost world, revealing forgotten Qing-era wars and reclaiming a historical narrative through overlooked artistry, Zhao Huanxin reports from Washington.

Capturing raw authenticity

Beyond their value as visual history, Kuang argues these works represent a "lost chapter" that could rewrite Chinese art history.

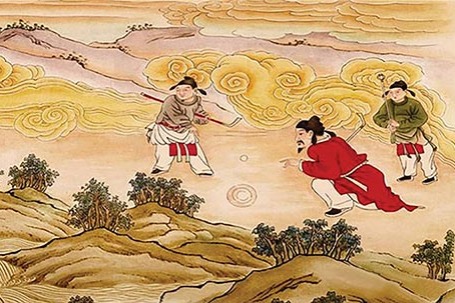

He divides Qing oil paintings into two broad streams: court paintings produced by Western missionaries like Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) under strict imperial supervision, and Guangdong export paintings that captured the raw authenticity of Chinese life, far exceeding court art in scale and scope.

This isn't just a matter of aesthetics; it is a matter of correcting the record of Chinese intellectual and artistic evolution and acknowledging a vibrant, commercial art scene that thrived outside the palace walls.

One of his prized examples is the Portrait of Wu Guoying in Casual Attire, painted around 1800. Wu founded the powerful Ewo Hong, one of the leading firms in the Thirteen Hongs.

Capturing the merchant with surgical precision, the artist rendered a lifelike presence that Kuang considers a pinnacle of global oil painting for its time.

He points to the way the light catches the silk of the robe and the weary, intelligent expression in the merchant's eyes.

This chapter remains absent from textbooks largely because the physical evidence drifted overseas, and anonymous masters were too embarrassed to sign their names to what the elite dismissed as a "minor trick".

"The history of oil painting in China should be moved back by about 100 years," Kuang says.

This conviction was reinforced when Gong Naichang, a student of renowned artist Xu Beihong (1895-1953), viewed the portrait.

According to Kuang, the elder artist's hands shook as he studied the canvas; Gong admitted that no one in his teacher's generation could have painted with such anatomical depth.